Introduction:

Introduction:

[6]

[6]

[8]

"You still don't understand what you're dealing with, do you? The perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility. I admire its purity. A survivor … unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality."

- Ash to Ripley (Alien, 1979)

Introduction:

Introduction:

[6]

[6]

Introduction

Have you ever gone swimming in any warm freshwater lake, river, or hot springs recently? Perhaps Lake Lanier? If your answer is yes then I am sorry to inform you but there is a chance you are infected with Naegleria fowleri (N. fowleri)! Better act quickly because this infection is deadly and usually causes death within 1-12 days! However, before I scare you too much, there is some good news. Our body does a pretty good job of fighting the encounter with the parasite before it can actually lead to infection. Between the years 2000 to 2009 only 30 infections were reported in the U.S [1]. That is a low number considering the high exposure one has with this interesting parasite.

Have you ever gone swimming in any warm freshwater lake, river, or hot springs recently? Perhaps Lake Lanier? If your answer is yes then I am sorry to inform you but there is a chance you are infected with Naegleria fowleri (N. fowleri)! Better act quickly because this infection is deadly and usually causes death within 1-12 days! However, before I scare you too much, there is some good news. Our body does a pretty good job of fighting the encounter with the parasite before it can actually lead to infection. Between the years 2000 to 2009 only 30 infections were reported in the U.S [1]. That is a low number considering the high exposure one has with this interesting parasite. Symbiont Description

N. fowleri is a member of the subphylum Sarcodina and superclass Rhizopodea. The superclass Rhizopodea includes several species of amebas. The genus Naegleria includes several species, however, only N. fowleri is known to produce human disease [2]. N. fowleri is a free-living organism, meaning that they can survive without a host. This is a great advantage to the parasite and explains why their attacks are fatal [4]. Hosts are necessary for survival of parasites that are not free-living. They have to think twice before killing the host. N. fowleri, on the other hand, can survive without a host and so do not have to avoid killing them.

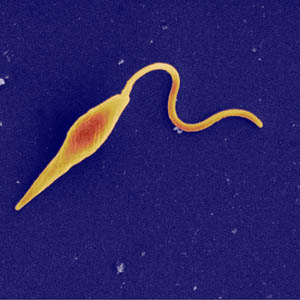

An interesting aspect of this parasite is that it has both a flagellated and unflagellated form. More specifically it has two flagella. During the flagellated stage it does not feed. In laboratory tests, N. fowleri loses the flagella when placed in distilled water. The ameba gains the flagella again when there is a change in the environment. During unfavorable conditions the amoeba can also form cysts and this allows it to survive harsh conditions. Image: [5]

An interesting aspect of this parasite is that it has both a flagellated and unflagellated form. More specifically it has two flagella. During the flagellated stage it does not feed. In laboratory tests, N. fowleri loses the flagella when placed in distilled water. The ameba gains the flagella again when there is a change in the environment. During unfavorable conditions the amoeba can also form cysts and this allows it to survive harsh conditions. Image: [5] For parasites like N. fowleri that thrive in oxygenated environment, the brain, which is oxygenated tissue, is the perfect home. However, finding a way into this nurturing environment is a challenge.

The brain has an especially more protective barrier called the blood-brain barrier.This barrier is made of cells that make a tight seal along blood vessels that prevent mostly everything from the bloodstream, which includes brain parasites like N. fowleri, from leaking through [6]. Unfortunately for us, N. fowleri rise up to the challenge very well. So how do they enter the brain? [Image [7]

The brain has an especially more protective barrier called the blood-brain barrier.This barrier is made of cells that make a tight seal along blood vessels that prevent mostly everything from the bloodstream, which includes brain parasites like N. fowleri, from leaking through [6]. Unfortunately for us, N. fowleri rise up to the challenge very well. So how do they enter the brain? [Image [7]

The attack:

The parasite attaches to the inside of the host’s nose and follows the olfactory nerve path to reach the brain. When it has reached the brain, the damaging effects commence. N. fowleri crosses the barrier by actually eating the nerve cells.This is obviously very bad for the host and is the main reason for the rapid death. The parasite has surface proteins that allow it to cut a hole in the covering of the cell. When it pierces the hole the contents of the neuron leak out and the parasite feed on the nutrients it contains. Furthermore, this special parasite has proteins that are able to sense the presence of certain nutrients, and this causes it to send signals to the rest of the cell indicating in which direction the parasite should move to eat those nutrients [6].

The human body cannot detect the intrusion of the parasite in the brain because the parasite is able to avoid detection by another set of proteins called CD59. This prevents the parasite from being taken up by phagocytes or being destroyed [4]. In addition, there are other proteins on the surface that direct the parasite to the most vulnerable areas of a neuron [6].Basically this parasite has evolved its own GPS system of the human brain! What can our body do when our mind is being eaten alive? Image: [8]

The human body cannot detect the intrusion of the parasite in the brain because the parasite is able to avoid detection by another set of proteins called CD59. This prevents the parasite from being taken up by phagocytes or being destroyed [4]. In addition, there are other proteins on the surface that direct the parasite to the most vulnerable areas of a neuron [6].Basically this parasite has evolved its own GPS system of the human brain! What can our body do when our mind is being eaten alive? Image: [8]

Well the human body does a superb job of preventing the parasite from even getting so close to the brain and it does so by using snot! A primary defense of the body is to secret mucus so that the parasite cannot adhere and move up the nose. N. fowleri again rises up to this challenge by producing enzymes to digest the mucus, this process is called mucinolytic activity [6]. In the competition of mucus production versus the mucinolytic enzyme effectiveness the body does an exceptional job of trapping the parasites. This is supported based on how often we are exposed to this parasites and how often they actually cause infection.

Life Cycle

Life Cycle

The life cycle of N. fowleri has 3 stages. In the ameboid trophozite stage, the parasite feeds on bacteria and replicates through binary fission where the nuclear membrane remains intact. Replication can only occur in this stage. This is also the stage where human infection can occur. When there is a change in ionic concentration the

Some signs and symptoms of infection include stiffness, cramping and pain in the muscles of the back and neck. Weakness, severe headaches, seizures, nosebleeds, rapid and shallow breathing, swollen and painful lymph nodes is possible. Decreased appetite, loss of smell and problems tasting food, confusion, hallucinations, and difficulty with concentration may also be associated. [11]. Video: [12]

An Example of the Host’s Two Lines of Defense

N. fowleri’s host, the human body, displays the perfect example of the concept of a host having two lines of defense.The first line of defense is avoiding the parasite by appropriate behavior. If the encounter still does take place, the second line of defense is immunity, which is basically to expel the intruder.

So the next time you decide to go swimming in any warm freshwater lake make sure you bring nose plugs. You do not want Naegleria fowleri swimming up your nose and eating your brain! Image: [13]

References

[1]http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/naegleria/faqs.html

[2]http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/972044-overview

[3]http://www.flickr.com/photos/trenchcoatjedi/2285088742/

[5]http://en.academic.ru/dic.nsf/enwiki/288084#

[6]http://eands.caltech.edu/articles/LXVI4/brainworms.html

[7]http://www.colorado.edu/intphys/Class/IPHY3730/05cns.html#outline

[8]http://infomationhealth.blogspot.com/2010/10/living-creatures-that-can-live-in-our.html

[9]http://www.stanford.edu/class/humbio103/ParaSites2004/N.%20Fowleri/life%20cycle%20&%20morphology.htm

[10]http://www.ehagroup.com/resources/pathogens/acanthamoeba-spp-and-naegleria-fowlerimeningitis/

[11]www.polk.wateratlas.usf.edu/upload/documents/fact_sheetAmoebae.pdf

[12]http://health.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-brain-eating-amoeba.html

[13]http://casperswanders.blogspot.com/2010/11/nevada-desert-adventure-nanfa_12.html

n referred to as the oriental avian eye fluke. It was once thought that this parasite was only found in the eastern part of the world but we now know that the parasite is found on almost every continent. P. gralli is found in most bird species ranging from ducks to pigeons to ostriches. The parasite is ingested through the mouth of a bird that feeds on aquatic vegetation. From there the parasite travels to its final resting spot in the conjunctival sac of the bird’s eye. Once the parasite is in the eye, the bird will experience severe watery discharge from the infected eye. Other common signs of philophtalmiasis include swollen eyes or a mild edema. Humans may also be infected by this parasite, but they are considered an accidental host. However, human cases have been found in the United States, Central Europe, the Middle East and Southeast Asia and Japan. [1]

n referred to as the oriental avian eye fluke. It was once thought that this parasite was only found in the eastern part of the world but we now know that the parasite is found on almost every continent. P. gralli is found in most bird species ranging from ducks to pigeons to ostriches. The parasite is ingested through the mouth of a bird that feeds on aquatic vegetation. From there the parasite travels to its final resting spot in the conjunctival sac of the bird’s eye. Once the parasite is in the eye, the bird will experience severe watery discharge from the infected eye. Other common signs of philophtalmiasis include swollen eyes or a mild edema. Humans may also be infected by this parasite, but they are considered an accidental host. However, human cases have been found in the United States, Central Europe, the Middle East and Southeast Asia and Japan. [1] t: a snail. Thiara spp. and Melanoides spp. are believed to be two species of snails that are known to carry the parasite. From there the parasite reaches its finial host. The final host can be any number of birds. Research has shown an infection in ostriches in Zimbabwe [2] and baby ducks in Jordan [4] but those are not the only cases. An accidental host includes Humans, although this is not common. [1]

t: a snail. Thiara spp. and Melanoides spp. are believed to be two species of snails that are known to carry the parasite. From there the parasite reaches its finial host. The final host can be any number of birds. Research has shown an infection in ostriches in Zimbabwe [2] and baby ducks in Jordan [4] but those are not the only cases. An accidental host includes Humans, although this is not common. [1]The excerpt above is from an online news publication established in the United Kingdom. The author was told by her optician that if she did not keep her contacts clean, she would put herself at risk of contracting a “bug”, in this case Acanthamoeba Keratitis [1]. A. keratitis infection primarily occurs via the use of contact lenses, in particular poor contact hygiene (i.e. wearing contacts lenses while swimming or showering). Acanthamoeba causes three illness involving the eye (Acanthamoeba keratitis), the brain and spinal cord (Granulomatous Encephalitis), and infections that can affect the entire body (disseminated infection) [2]. A. Keratitis is not actually a bug, but rather an amoeba- a microscopic, unicellular eukaryotic organism that uses pseudopodia as a means of motility [3]. A. Keratitis resides in the cornea where it feasts on the proteins of the eye and bacteria that get trapped. Unfortunately, the immune system is unable to fight the parasitic invader because the cornea lacks blood vessels. Eventually, Acanthamoeba burrow into the eye, which leads to vision loss.

Symbiont Description:

Acanthamoeba is a type of free-living amoeba typically found in the environment. As stated before, an amoeba is a single-celled eukaryotic organism that lacks a set shape and travels from place to place using pseudopodia, which are projections of the cell (“false feet”). True to its eukaryotic nature, amoebae contain organelles encased in a cell membrane. It ingests nutrients using phagocytosis, which is a process characterized by the cell membrane forming projections that extend and surround a food particle until it is completely enclosed . Thereafter, the particle of food is encased in a vacuole, which digests it [3]. A. Keratitis feeds on the cornea of the eye- a transparent, complex of tissues consisting of proteins and cells that cover the outer surface of the eye. The cornea lacks blood vessels with which to protect the eye or provide nourishment. Instead, the cornea receives nutrients from the tear ducts. When the innermost layer of the cornea, the endothelium is destroyed, the cells cannot be repaired and blindness results [4]. A. Keratitis is partial to the cornea because without a steady flow of blood or lymph fluid, the immune system cannot attack a pathogen that infects the eye; thus, the parasite can eat and reproduce without the fear of attack.

Host Description

Acanthamoeba Keratitis is a free-living amoeba. It does not use an insect vector for transmission. A. Keratitis affects the human eye by water. Water is a hot commodity for humans; thus, A. Keratitis is spread via recreational pools, soil, sewage, air conditioning ventilation units, vegetables, and lakes to name a few. However, only one or two individuals out of a population of one million will contract A. Keratitis [6].

Life Cycle

Keratitis has only two stages in its life cycle. It forms cysts which develop into infective, mobile trophozoites (a growing phase of the amoeba). These trophozoites travel through a water source and reproduce via mitosis. The trophozoites enter the hosts via the eye, where they secrete proteins that break down the cornea’s surface allowing the amoebae to burrow into the tissue. The parasites then feed on the tissues of the host’s eye as well as bacteria on the eye. During this process the host is likely to experience pain, redness, swelling, blurred vision, and in some cases blindness [6].

Ecology

While A. Keratitis is rare, the impact it can have on its humans is devastating. Of the people who contract A. Keratitis in the United States 85% of contact users. Although, it is spread via water, using contacts properly can significantly reduce the risk of infection. Currently, there are no reports of A. Keratitis being spread from person to person [2].

Monsters Inside Me: A. Keratitis [8]

Monsters Inside Me: Parasites Invade Eyeball [9]

An Example of “Escaping Host Defenses”

According The Art of Being a Parasite A. Keratitis would have won the first round because it successfully establishes itself inside of a host. A. Keratitis escapes detection by the host’s immune system by inhabiting an organ that lacks blood or lymph vessels. In other words, A. Keratitis hides in organs that are classified as non-immunogenic, meaning that the organ does not have the ability to recognize a pathogen and induce an immune response [11].

References

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/acanthamoeba/gen_info/acanthamoeba.html

[3] http://www.bioscience-info.com/amoeba

[4] http://www.caister.com/supplementary/acanthamoeba/c4.html

[5] http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/html/imagelibrary/A-F/FreeLivingAmebic/body_FreeLivingAmebic_il2.htm

[6] http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside-me/acanthamoeba-keratitis/

[7] http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/acanthamoeba/biology.html

[8] http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-acanthamoeba-keratitis-parasite.html

[9] http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-acanthamoeba-keratitis.html

[10] http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside-me/acanthamoeba-keratitis/

[11] Combs, C. 2005. The Art of Being a Parasite. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

[1]

[1] [2]

[2]

[8]

[8] [10]

[10]

Example of Paragonimus westermani: Of the four categories of parasites, Paragonimus westermani is a parasitee Type D parasite. Type D parasites are passive in that they are ingested by the host, often with the host’s food. They become mesoparaistes. Some of them might puncture the wall of the digestive tract to become endoparasites [5].

References:

[1] http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/html/Paragonimiasis.htm

[2] http://www.parasitesinhumans.org/paragonimus-westermani-lung-fluke.html

[3] http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/images/ParasiteImages/M-R/Paragonimiasis/Paragonimus_LifeCycle.gif

[4] http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/sec14/ch183/ch183g.html

[5] Combes, Claude. "The Profession of Parasite." The Art of Being A Parasite. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2005. 51